- Beyond the Blade: Sport Performance & Wellness for Historical Fencers

- Posts

- Anterior Knee Pain

Anterior Knee Pain

How to Not Let it Sideline You From Fencing

Many fencers have felt it at some point in their career: a distinct ache at the front of the knee after a long night of footwork or waking up after a weekend tournament. If there’s no bruise or swelling in sight (and you didn’t get geysler’d in the knee) it may be tempting to call it just “overuse pain.” But that front-of-knee discomfort, or what we generally call anterior knee pain is often a signal from your body that the load on your knee has gotten out of balance.

Especially if it starts occuring on a daily basis, or comes and goes with your weekly fencing classes it’s time to dig a little deeper and address the contributing factors before it sidelines you. The good news: Most mild cases can be fixed (and prevented) with a few adjustments in training and a little extra work in the gym. The bad news: If you ignore it and keep grinding through practice and tournaments, you risk turning a minor overload into something that eventually knocks you out of training (and other fun activities) for weeks.

So this week, let’s talk about what’s really going on around that kneecap and what you can do about it as a coach or student.

Jump to a Section

Research Corner

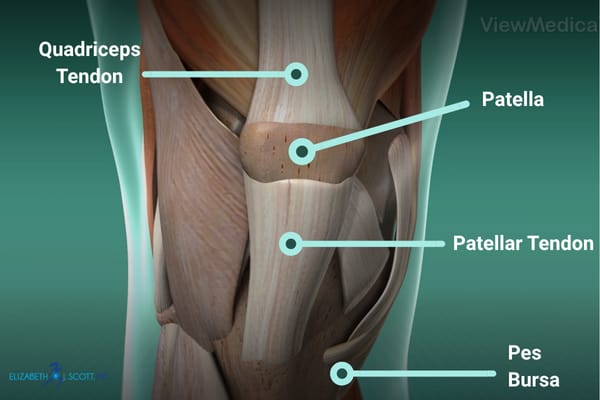

Part of what makes anterior knee pain so nebulous and confusing is that within a relatively small area we have several anatomical structures linking together. All of them can cause problems in fencers, and it’s important to recognize them as distict structures. Here are some of the most common culprits of mild front-of-knee pain:

Patellar tendinopathy (“jumper’s knee”) overload of the patellar tendon complex living just below the kneecap. The tendon may feel sore to touch along its entire path, or just at the top. Sometimes accompanied by crepitus (crunchy/poppy feelings), stiffness, or mild swelling.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) irritation related to the kneecap (patella) gliding within its its groove. Often this can be from very minor imbalances in the tracking proccess which is magnified by the thousands of times a knee bends and extends in a day or fencing practice. This is a distinct condition from the less common (but more serious) problem of patellofemoral instability, where the kneecap physically dislocates out of its groove. PFPS is often a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning the more serious things like cartilage damage or instability have been ruled out.

Pes anserine tendinopathy or bursitis – inflammation on the inside/front of the knee where hamstrings and adductors insert. The “pes” is the insertion of these muscles. Common in sports with quick direction changes and rotational or lateral movements, particularly after a sudden increase in training volume.

Although each has a slightly different location, pathophysiology, and affected population, all three share a common theme: too much stress at the front of the knee compared to how much support the hips and hamstrings are giving it. In other words, a mismatch in the forces being distributed through and around the kneecap, and the flexibility and strength of the supporting muscles. The problem in some ways isn’t with the area that hurts - it’s the entire kinetic chain supporting it. The kneecap or area around it has simply become the weakest link.

Typically the problem has multiple contributing factors, such as:

Tight hamstrings, adductors and/or glutes

If your glutes or hamstrings are tight, they can pull on the pelvis and change the angle of your femur and tibia when you bend the knee. That subtle shift increases pressure between the kneecap and femur, and increases tension across the tendons which span the knee, including the patellar and pes tendons. For fencers, that means every deep lunge or crouch happens with the knee slightly “off-track.” Over time, that extra shear and compression can flare up the front of the knee even if your strength work is on point. More often however this goes together with under-recruitment of the posterior chain muscles (see #2).

Overly-dominant quadricep (and weak posterior chain)

If your glutes and hamstrings are under-trained, your quadricep muscles take over to get the job done. That shifts the load forward, increasing compression behind the kneecap and tension on the patellar tendon. While this might be ok for a few reps of an exercise, in rounds of sparring day after day this can build up to become a significant problem.

Before the pain starts, subtle signs of this phenomenon include a tendency for the knee to collapse slightly inward during footwork or lunges, and a too-forward weight stance during sparring where the back foot isn’t equally loaded (and the back leg hamstring isn’t really engaged). This can be tricky to spot. Some fencers may start off a training session with great mechanics but degrade as the rounds or matches progress. This is one (of several ) reasons I often recommend fencers “leave one in the tank” on sparring days and retire before they feel completely spent. If you’re not sure, check a video of yourself fencing at the beginning of a tournament weekend or long practice and compare it to your last fight at the end. Do you see subtle changes in your stance, footwork, or mechanics?

Sudden Change in Training Volume

A jump in training volume or intensity, like doubling up on footwork drills before a tournament, starting a new lifting program, adding in an additional class per week, or returning to training after time off can overload tissues that aren’t yet adapted. Tendons respond best to gradual, progressive stress. This is why achilles tendonitis or plantar fasciitis can be so frustrating - there’s no way to speed up the proccess. In our body it is typically the muscle-tendon or tendon-bone connection that is the weakest part of the chain. When you ramp up faster than your body’s capacity to recover, the tendon absorbs more force than it can handle, microtears occur, and inflammation and pain follows.

HEMA Hot Take:

Got that pain I was talking about? Here’s an approach to getting it to resolve before it becomes a game-limiting problem.

1. Dial Down the Load

Reduce volume on the knee. Avoid deep lunges, loaded jumps/squats in the gym, and explosive footwork for a week or two. Try lower-impact drills and technique-focused work like pell work or lower-intensity bladework drills. You can also replace some of that time with dedicated strength and conditioning to protect the knee (see #3).

2. Mobilize the Tissue

Flexible and strong muscles share the load more evenly and keep your knees happier. Try adding dynamic hip and hamstring mobility to your warm-ups, like leg swings, deep squat rotations, and 90-90 hip shifts. Follow with glute & hamstring activation before training. You can also explore some manual therapy, light stretching or foam rolling of the quads, hamstrings, calves, and IT band to relieve some of the tension pulling on the kneecap and surrounding tendons. Although there is great debate about the utility and timing of heat and cold therapy, my general rule is if it feels good, use it.

3. Strengthen the Posterior Chain

Some stretches and a couple days off aren’t going to help an underlying muscle imbalance. A few key moves that could enter your routine and can help build a strong posterior chain are below but this is certainly not an exhaustive list. From bodyweight and bands to trap bar and machines, there are a myriad of ways to work on your adductor, vastus medius, glute, and hamstring strength. If in doubt, schedule a session with a physio who can craft a routine for you based on your specific gym equipment and setup.

Added bonus to this work? It will probably benefit your fencing. The posterior chain muscles are what help you create immense power and push-off to perform big movements like a ballestra, fleche, or grappling & throw. 2-for-1 gain to time spent in the gym!

Exercise | Purpose | How To |

|---|---|---|

Glute + hamstring strength; balance | Hinge at hips, soft knee, keep spine neutral | |

Eccentric posterior chain strength and torso control | Nordbord or Swedish Ladder setup (see video) | |

Posterior chain power and pelvis control | Squeeze glutes at top, avoid arching. | |

Step Downs | Eccentric quad control and knee tracking | Stand sidways on a 6-8” step and slowly lower one heel to the floor without collapsing the knee or hip |

Glute med strength and hip extensors | with band around the ankles, stand on one leg and make slow circles with the other |

Coach’s Corner

When your glutes and hamstrings aren’t strong enough or fatigue early during long bouts, the quadriceps take over instead. That shifts the load forward, increasing compression behind the kneecap and tension on the patellar tendon and other structures.

As coaches, one thing we can do to help our students is to make sure they are engaging their hips and core appropriately when they engage in a grapple, push off and land in a lunge, or turn and pivot.

Things to watch for:

During lunges or squats, watch for an upright torso centered evenly over both legs. Avoid significant drift of the knee over the toe (a sign the front leg is overloaded), or collpasing and over-hinging at the hips in effort to reach a longer distance.

Watch for valgus collapse (knee dropping inward) of either the front or back knee in a lunge - a sign of weak glute medius (and/or inexperience with the movement pattern).

Emphasize control before speed in footwork drills.

End repetitions of an exercise before form degrades significantly. That may mean ending an exercise sooner than you’d like in order to protect the most inexperienced members of the class, who are most at risk of form issues. Similarly, encourage fencers to bow out of sparring once they feel close to their limit, not beyond it.

Health & Fitness Tips

When to Call the Doc (or see the Physio)

Head in to see a sports physical therapist or physician if you notice:

⚠️ Deep clicking, locking, or catching in the knee

⚠️ Sudden swelling or sharp pain after a single event

⚠️ True instability or “giving way” of the knee or hip

⚠️ Pain that worsens instead of improving after a week of rest

⚠️ Night pain, warmth, or redness around the joint

If it’s not improving, or it feels different from normal “aches and pains” soreness please get evaluated. Persistent pain or mechanical symptoms might indicate meniscal injury, ligament sprain, or cartilage/bony problem, all of which should be evaluated with a hands-on examination and potentially imaging.

Conditioning Move of the Week

Hip Windshield Wipers to Spinal Twist

This mobility drill targets hip internal/external rotation and thoracic spine mobility. Improving hip rotation helps with footwork and lunge mechanics, while thoracic mobility reduces shoulder compensation and low back stress. Include this move in your warmup and cooldown to maintain mobility in the hips and encourage fluid movement thorughout the full range of motion.

Upcoming Events

🔥 Strength & Steel Our newest program for intermediate & advanced HEMA fencers. With a basic home gym setup and 3 hours a week, you can develop power, speed, and endurance that translates to the ring. | 💥 1:1 Coaching Spots OpenI have ONE opening currently for private training starting mid-November. Take the guesswork out of your conditioning training and get fully customized workouts that fit your schedule, your goals, your equipment. Email me or head to the Sprezzatura Sports website to learn more. |

Anterior knee pain is rarely “just bad luck” (unless you just tripped over your fencing bag and landed on it). In fencers, sneaky front of the knee pain is often a sign that the hips and hamstrings are under-recruited and the front of the knee is taking the brunt of the force. Address it early with a good strength program or appropriate medical care, and before you know it you’ll move with more speed, stability, and longevity on the strip (and in armor).

Have someone you know who might benefit from this article? Forward it to them and share the gain 💪

Coach Liz

Reply